The Shakespeare Authorship Question

For hundreds of years there has been academic debate on the subject of the true authorship of the works of William Shakespeare.

People such as Einstein, Freud, Charles Dickens, Mark Twain, Henry James and many others have publicly expressed skepticism in regard to prevailing academic opinion that William Shakespeare authored the works of Shakespeare.

You can read this excellent Wikipedia page on the subject.

Or an edited version of this and several other Wikipedia pages here below.

Why Is There An Authorship Question At All?

Perhaps it's necessary to ask, 'Why should there be an authorship question at all?'

Elizabethan England kept extremely good records. Better than anyone until modern times.

In other countries there is no confusion over the authorship of Dante or Goethe, or over Milton in England. The only confusion is over Shakespeare.

Since Shakespeare left a towering body of work, we would expect there to be a great amount of documentation of his comings and goings.

He lived in a London of only 200,000 people and his estimated book sales over his lifetime have been placed at 50,000. Even at half that number, Shakespeare is an extreme bestselling author in a mainly illiterate society.

He was the most famous and celebrated man in the kingdom, rivaled only by the Earl of Essex and Sir Walter Raleigh. And yet there is almost nothing in Elizabethan records concerning his life, thought or actions. Not even in the informal diaries of his peers and friends. There are perhaps a total of a dozen mentions over a period of 25-30 years, all spent at the heart of the London theater as a superstar.

This suggests that, whatever was occurring, it was something out of the ordinary.

This is why the record is unclear, something unusual was taking place in regard to the authorship of the plays, allowing the authorship question to arise, by virtue of the mysteriously missing documentation of Shakespeare’s life.

This suggests that in his time, Shakespeare was a public pseudonym, whose real identity was unknown to the public at large.

Probably this was explained by the believable suggestion that he was of noble birth, and therefore forced to write lowly theater drama anonymously.

The Contenders For Authorship:

William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon, (baptised April 1564; died 23 April 1616)

The Chandos portrait, artist and authenticity unconfirmed.National Portrait Gallery, London.

William Shakespeare (baptised 26 April 1564; died 23 April 1616)[a] was an English poet and playwright, widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist.[1] He is often called England's national poet and the "Bard of Avon".[2][b] His surviving works, including some collaborations, consist of 38 plays,[c] 154 sonnets, two long narrative poems, and several other poems. His plays have been translated into every major living language and are performed more often than those of any other playwright.[3]

Recent new research (2009-2010) by Lee Vidor conclusively proves that William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon did not write the plays or poetry attributed to his name.

Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, (12 April 1550 – 24 June 1604)

Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford (12 April 1550 – 24 June 1604) was an Elizabethan courtier, playwright, poet, sportsman, patron of numerous writers, and sponsor of at least two acting companies, Oxford's Men and Oxford's Boys,[1] and a company of musicians.[2] He was born at Castle Hedingham to the 16th Earl of Oxford and the former Margery Golding.

Oxford was one of the leading patrons of the Elizabethan age and, during his lifetime, 33 works were dedicated to the Earl, including publications on religion, philosophy, medicine and music. The focus of his patronage, however, was literary, with 13 of the books presented to him either original or translated works of world literature.

The most popular modern candidate is Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford.[192] This theory was first proposed by J. Thomas Looney in 1920, whose work persuaded Sigmund Freud, Orson Welles, Marjorie Bowen, and many other early 20th-century intellectuals. The theory was brought to greater prominence by Charlton Ogburn's The Mysterious William Shakespeare (1984), after which Oxford rapidly became the favored alternative to the orthodox view of authorship. Advocates of Oxford are usually referred to as Oxfordians.

Oxfordians base their theory on what they say are multiple and striking similarities between Oxford's biography and events in Shakespeare's plays and sonnets, in particular incidents found in Hamlet, The Merchant of Venice, Timon of Athens, The Taming of the Shrew and All's Well That Ends Well. They also cite his intimacy with Queen Elizabeth I, the Earl of Southampton, court life, his record of travel throughout France and Italy, including to cities used as settings for some of Shakespeare's plays,[193] and his dramatic financial downfall.[194] Oxfordians also point to his extensive education and acknowledged intelligence; the contemporary acclaim of Oxford's talent as a poet and a playwright and his reputation as a concealed poet; the purported parallel phraseology and similarity of thought between Shakespeare's work and Oxford's extant letters and poetry;[195] and underlined passages in his Bible in which they see correspondences to themes and expressions in Shakespeare's plays.[196]

Supporters of the orthodox view say that incidents in the plays fit many other aristocrats of the day, such as William Stanley, 6th Earl of Derby (who also is nominated as an authorship candidate based on biographical parallels found in the works),[197] King James, and the Earl of Essex, and therefore consider this method invalid for attributing authorship.[198] But they say that the most compelling evidence against Oxford is his death in 1604, before a number of Shakespeare's plays were written, according to the orthodox dating of the canon. Oxfordians, and some orthodox scholars, respond that the plays are dated to fit Shakespeare of Stratford's known lifespan, and assert that there is no conclusive evidence that the plays or poems were written after 1604, and that in fact no sources used by Shakespeare after that date have been positively identified.[199] (For a dating of Shakespeare's plays according to the Oxfordian theory, see Chronology of Shakespeare's plays – Oxfordian.)

Mainstream Shakespearean critics also assert that Oxford's known poems bear no stylistic resemblance to the works of Shakespeare,[200] but Oxfordians point out that the poetry published under his name is juvenilia, that of a very young man, citing parallels between Oxford's poetry and Shakespeare's early play, Romeo and Juliet.[195] Researcher Kurt Kreiler writes that Oxford’s juvenilia "represent the path to Shakespeare and already foreshadow the sedulous stylist that Shakespeare was to become."[201]

For a detailed Oxfordian examination of the parallels between Shakespeare's plays and Oxford's biography, see Oxfordian theory: Parallels with Shakespeare's plays

Sir Francis Bacon, (22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626)

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban, KC (22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626), son of Nicholas Bacon by his second wife Anne (Cooke) Bacon, was an English philosopher, statesman, scientist, lawyer, jurist, and author. He served both as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England. Although his political career ended in disgrace, he remained extremely influential through his works, especially as philosophical advocate and practitioner of the scientific revolution.

In 1856, William Henry Smith put forth the claim that the author of Shakespeare's plays was Sir Francis Bacon, a major scientist, philosopher, courtier, diplomat, essayist, historian and successful politician, who served as Solicitor General (1607), Attorney General (1613) and Lord Chancellor (1618).

Smith was supported by Delia Bacon in her book The Philosophy of the Plays of Shakespeare Unfolded(1857), in which she maintains that Shakespeare's work was in fact written by a group of writers, including Francis Bacon, Sir Walter Raleigh and Edmund Spenser, who collaborated for the purpose of inculcating a philosophic system for which they felt that they themselves could not afford to assume the responsibility. She professed to discover this system beneath the superficial text of the plays. Constance Mary Fearon Pott (1833–1915) adopted a modified form of this view, founding the Francis Bacon Society in 1885, and publishing her Bacon-centered theory in Francis Bacon and His Secret Society (1891).[202]

Since Bacon commented that play-acting was used by the ancients "as a means of educating men's minds to virtue,"[203] a non-esoteric view is that Bacon acted alone and to serve his Great Instauration project[204] he left his moral philosophy to posterity in the Shakespeare plays (e.g. the nature of good government exemplified by Prince Hal in Henry IV, Part 2). Having outlined both a scientific and moral philosophy in his Advancement of Learning, only Bacon's scientific philosophy was known to have been published during his lifetime (Novum Organum 1620).

Supporters of Bacon draw attention to similarities between specific phrases from the plays and those written down by Bacon in his wastebook, the Promus,[205] which was unknown to the public for more than 200 years after it was written. A great number of these entries are reproduced in the Shakespeare plays, often preceding publication and the performance dates of those plays. Bacon confesses in a letter to being a "concealed poet"[206] and was on the governing council of the Virginia Company when William Strachey's letter from the Virginia colony arrived in England which, according to many scholars, was used to write The Tempest. There is also evidence that it was not Shakspere's company that played the first known performance of The Comedy of Errors on Innocent's Day 1594-5, but the Gray's Inn Players, and there is further evidence that Bacon controlled this (see Baconian theory).

Despite Percy Bysshe Shelley's testimony that "Lord Bacon was a poet",[207] the main argument usually levelled against Bacon's candidacy is that the little poetry that has been attributed to Bacon is abrupt and stilted, unlike Shakespeare's.[208] It has also been noted that Bacon was still living when the Sonnets were published in 1609, yet he made no effort to claim them or to collect royalties on them.[209]

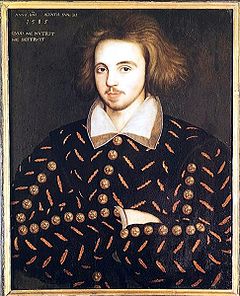

Christopher Marlowe, (c. 26 February 1564 – 30 May 1593)

Christopher Marlowe (c. 26 February 1564 – 30 May 1593) was an English dramatist, poet and translator of the Elizabethan era. The foremost Elizabethan tragedian next to William Shakespeare, he is known for his blank verse, his overreaching protagonists, and his mysterious death.

A case for the gifted young playwright and poet Christopher Marlowe was made as early as 1895, but the creator of the most detailed theory of Marlowe's authorship was Calvin Hoffman, an American journalist whose main argument centres on the use of similar wordings or ideas—called "parallelisms"—between the two writers.[210] A.D. Wraight also wrote an influential book promoting Marlowe as the author, but she delves more into what she sees as the true meaning of Shakespeare's sonnets.[211]

Marlowe created a stir with his literary output while attending Cambridge as a scholarship student. The young writer was the first to translate Ovid's Amores into English – translations which were subsequently ordered publicly burned by the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Bishop of London.[citation needed] His translation and adaptation into blank verse of Lucan's Pharsalia is one of the earliest English verses written in unrhymed iambic pentameter, and has influenced poets from Milton to Wordsworth.[citation needed] While still a university student, Marlowe's play Doctor Faustus was produced in London; shortly after he earned his M.A. and left Cambridge, his play Tamburlaine the Great appeared on the London stage for 200 performances.[citation needed]

Marlowe was said to have been murdered in 1593 by a group of spies, including Ingram Frizer, a servant of Thomas Walsingham, Marlowe's patron. A theory has developed that Marlowe, who may well have been facing an impending death penalty for heresy, was saved by the faking of his death (with the aid of people in high places such as Thomas Walsingham and Marlowe's possible employer, Lord Burghley) and that he subsequently wrote the works credited to William Shakespeare while in exile in Italy. Hoffman argued that Shakespeare of Stratford was paid by the conspirators to sign his name on the manuscripts, to conceal the fact that Marlowe was still alive.[citation needed]

Supporters of Marlovian theory also point to stylometric tests and studies of parallel phraseology, which sought to show how "both" authors used similar vocabulary and a similar style.[citation needed]

Mainstream scholars find the argument for Marlowe's faked death unconvincing. They also find the writings of Marlowe and Shakespeare very different, and attribute any similarities to the popularity and influence of Marlowe's work on subsequent dramatists such as Shakespeare

William Stanley, 6th Earl of Derby, (1561–1642)

William Stanley, 6th Earl of Derby (1561 – 29 September 1642) was an English nobleman.He was a son of Henry Stanley, 4th Earl of Derby and Lady Margaret Clifford. His mother was heiress presumptive of Elizabeth I of England from 1578 to her own death in 1596.

One of the chief arguments in support of Derby's candidacy is a pair of 1599 letters by the Jesuit spy George Fenner in which it is reported that Derby is "busy penning plays for the common players." Professor Abel Lefranc (1918) claimed his 1578 visit to the Court of Navarre is reflected in Love's Labour's Lost. His older brother Ferdinando Stanley, 5th Earl of Derby formed a group of players which evolved into the King's Men, one of the companies most associated with Shakespeare. It has been theorized that the first production of A Midsummer Night's Dream was performed at his wedding banquet.

Born in 1561, Stanley's parents were Henry, Lord Strange, and Margaret Clifford, great granddaughter of Henry VII, whose family line made Stanley an heir to the throne. At the age of eleven, he went to St. John's College, Oxford. He later studied at both London law schools, Gray's Inn and Lincoln's Inn. He married Elizabeth de Vere, daughter of Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford and Anne Cecil.[213] Elizabeth's maternal grandfather was William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley, the oft-acknowledged prototype of the character of Polonius in Hamlet. Derby was also closely associated with William Herbert, 3rd Earl of Pembroke and his brother Philip Herbert, Earl of Montgomery and later 4th Earl of Pembroke, the two dedicatees of the 1623 Shakespearean folio. Around 1628 to 1629, when Derby released his estates to his son James, who became the 7th Earl, the named trustees were Pembroke and Montgomery.

Asserting a similarity with the name "William Shakespeare",

supporters of the Stanley candidacy note that Stanley's first name was

William, his initials were W. S., and he was known to sign himself,

"Will". They also cite biographical parallels between his life and

incidents in the plays.[214] In 1599 he is was reported as financing one of London's two children's

drama companies, the Paul's Boys and, his playing company, Derby's Men,

known for playing at the "Boar's Head". In addition the company played

multiple times at court in 1600 and 1601.[215] Stanley is often mentioned as a leader or participant in the "group theory" of Shakespearean authorship.[216]

Fulke Greville, Lord Brooke, (1554-1628)

Fulke Greville, 1st Baron Brooke, de jure 13th Baron Latimer and5th Baron Willoughby de Broke (3 October 1554 – 30 September 1628), known before 1621 as Sir Fulke Greville was an Elizabethan poet, dramatist, and statesman.

Fulke Greville was an aristocrat, courtier, statesman, sailor, soldier, spymaster, literary patron, dramatist, historian and poet. He was educated at Shrewsbury and Jesus College, Cambridge. He worked for Sir Francis Walsingham as an ‘intelligencer’ where he traveled extensively throughout Europe. He became a great favorite of Queen Elizabeth, was Clerk to the Council of Wales, Treasurer of the Navy, and from 1614-1621 he was Chancellor of the Exchequer.

After the death of his father in 1606, Fulke became Recorder of Stratford-upon-Avon and he held that post until 1628. Greville was famous for his friendship with, and biography of Sir Philip Sidney, and his long tempestuous love affair with Philip’s sister, Mary Herbert, Countess of Pembroke.

Greville is regarded as a generous patron of many of the leading writers of the day including Christopher Marlowe, Thomas Nashe, Samuel Daniel and three Poets Laureate; Edmund Spenser, Ben Jonson and Sir William Davenant. Greville was a member of all the leading literary circles of the day: The Areopagus, the Wilton House Circle, The Southampton Circle, the University Wits (associate) and The School of Night. He is also famous for his claim to have been the ‘Master of Shakespeare’ and the author of a ‘lost’ play called Antony and Cleopatra.

Sir Henry Neville, (c. 1562 - July 10, 1615)

Sir Henry Neville (c. 1562 - July 10, 1615) was an English politician, diplomat, courtier and distant relative of William Shakespeare.[1][2] In 2005, he was put forward as a candidate for the authorship of Shakespeare's works.

Neville (nicknamed Falstaff)[3] is a candidate for being the true writer of Shakespeare's works. Mainstream Shakespearean scholarship does not accept that anyone but William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon was the author; however, there exist a number of theories that the works were penned by someone else, in spite of the fact that not a single contemporary document exists that conflicts with Shakespeare's authorship.

In The Truth Will Out, published in 2005, authors Brenda James, a part-time lecturer at the University of Portsmouth, and Professor William Rubinstein, professor of history at Aberystwyth University, propose that Henry Neville, a contemporary Elizabethan English politician who was a distant relative of Shakespeare, is the true author. According to James and Rubinstein, Neville's career placed him in the locations of many of the plays about the time they were written, and his life contains parallels with the events in the plays.[4]

The book outlines the case for Neville as the true author, proposing that otherwise inexplicable features of Shakespeare's works thus make sense. For example, many of Shakespeare's plays are histories that revolve around the Plantagenets--the long-ago-defeated enemies of the (then) current regime in England. According to James, the choice of subject makes little sense with Shakespeare the author, but perfect sense if the author was Sir Henry Neville, a descendant of John of Gaunt and member of the Plantagenet family.

The book contends that, in many respects, Neville is a match for authorship. He had traveled extensively to places described in the plays, in particular Italy; was fluent in Italian, French, Latin, and most other current European languages; had a detailed knowledge of both court protocol and law; and in many other respects matches the educational knowledge and societal norms exhibited by the author of the plays.[5]

"The Truth Will Out" cites circumstantial documentary evidence that Neville was the author, notably the "Tower Notebook", a collection of writings by a prisoner in the Tower of London, presumably Neville.[6] The notebook contains writings similar to the stage directions for the coronation of Anne Boleyn in the play "King Henry VIII".

Mary Sidney, Countess of Pembroke, (1561-1621)

Mary Herbert, Countess of Pembroke née Mary Sidney (Bewdley, 27 October 1561 – London, 25 September 1621), was one of the first English women to achieve a major reputation for her literary works, translations and literary patronage.

A theory that Mary Sidney wrote the sonnets and some of the poetry and plays attributed to William Shakespeare has been revived by independent American scholar Robin P. Williams.[3] According to Williams, Mary Sidney had the scholarship, ability, motive, means and opportunity to write the plays. This is one among many alternative authorship theories which Samuel Shoenbaum's work has shown were originally fueled in the 19th century, in part due to a lack of knowledge about the curriculum in Elizabethan grammar schools. Mary's erudite brother, Sir Philip Sidney, attended Shrewsbury Grammar School and recently, scholars have demonstrated that Elizabethan grammar schools, like Stratford-upon-Avon's, provided a high level of classical education. The Sidney children were offered an extensive education at home. Computer analysis of Shakepearean language has Warwickshire words and imagery from kitchen gardens.[citation needed] An in-depth analysis of imagery (which in Shakespeare is concrete and homespun) will be part of interesting research. In the Sonnets, the author may be heard lamenting the use of the same poetic form. Mary Sidney's natural taste is for a very extensive variety of verse forms. Aemilia Lanier writes about Mary Sidney making others famous.

Another argument is the writer of the Shakespearean works seems to be very familiar with the landscape of Italy and some other countries which contradicts with the fact that Shakespeare never left England nor had any accurate maps available. Sidney is known to have traveled sometimes to Europe's spa's and for sure a lot of those taking part in her circle are known to have traveled a lot there or are originating from there.[citation needed]

Mary Sidney has been called a predominantly lyric poet, translator and religious writer, interested in morality and divine learning, filled with "Sidneian fire" as mentioned above. Shakespeare's focus can be said to be on dramatic, psychoanalytical and poetic representations of the twists of human personality, with a focus on evil, violence, love, murder, bonding, sexual passion and on "the concrete surface of the earth". Some have said Shakespeare's main inspiration was Ovid and there is extensive knowledge of the Bible, Italian literature, and the Classics. William Shakespeare and Mary Sidney may have met and known one another.[citation needed] He had clearly read her plays and translations. Mary Sidney's secretary, Sir John Davies penned a poem on William Shakespeare. It is one of the most complimentary pictures of the playwright, calling him a companion "fit for a king" and a "king among the lower sort" thanks to his "reigning wit".

In 2006, Canadian librarian Fred Faulkes published the first volume in The Tiger Heart Chronicles – a "narrative reconstruction of everything touching on Shakespearean history" in which he also put forward the Sidney claim.[4]

However, a more conservative observation is that The Countesse of Pembroke’s Arcadia (written in the main by her brother, Sir Philip Sydney) at least contributed to Shakespeare’s King Lear, Hamlet and The Winter’s Tale as a sourcebook

Queen Elizabeth I of England, (1533-1603)

Elizabeth I (7 September 1533 – 24 March 1603) was Queen of England and Queen of Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death. Sometimes called the Virgin Queen, Gloriana, or Good Queen Bess, Elizabeth was the fifth and last monarch of the Tudor dynasty. The daughter of Henry VIII, she was born a princess, but her mother, Anne Boleyn, was executed two and a half years after her birth, and Elizabeth was declared illegitimate. Her brother, Edward VI, bequeathed the crown to Lady Jane Grey, cutting his sisters out of the succession. His will was set aside, and in 1558 Elizabeth succeeded the Catholic Mary I, during whose reign she had been imprisoned for nearly a year on suspicion of supporting Protestant rebels.

Group Theory

In the 1960s, the most popular general theory was that Shakespeare's plays and poems were the work of a group rather than one individual. A group consisting of De Vere, Bacon, William Stanley, Mary Sidney, and others, has been put forward, for example.[217] This theory has been often noted, most recently by renowned actor Derek Jacobi, who told the British press "I subscribe to the group theory. I don't think anybody could do it on their own. I think the leading light was probably de Vere, as I agree that an author writes about his own experiences, his own life and personalities."[218][219]

Other Candidates

At least fifty other candidates have also been proposed.

A less well known candidate, William Nugent, was first put forward in Ireland by the distinguished Meath historian Elizabeth Hickey[222] and was expanded upon by Brian Nugent in his 2008 publication, Shakespeare was Irish!. William Nugent (1550–1625) was a nobleman from Delvin in County Westmeath who was imprisoned by the state for opposing the cess in Ireland in the 1570s, and he rebelled in 1581 losing a number of supporters to the hangman's noose and causing him to flee into exile, first into Scotland, then France and Italy.[223] During his exile he met with most of the great European leaders, such as the Pope, the King's of Spain, France and Scotland, and the Duke of Guise, and was involved in European-wide planning for an invasion of England.[224] He was known for his great literary talents, as described by Irish historian John Lynch: "he learnt the more difficult niceties of the Italian language and carried his proficiency to that point that he could write Italian poetry with elegance. Before that however he had been very successful in writing poetry in Latin, English and Irish and would yield to none in the precision and excellence of his verses in each of these languages. His poems which speak for themselves are still extant."[225] As early as 1577 he was known as a composer of "divers sonnets" in English, to quote his friend Richard Stanihurst writing in Chapter 7 of Holinshed's Chronicles.

In 2007, The Master of Shakespeare by A. W. L. Saunders proposed a "new" candidate — Fulke Greville, 1st Baron Brooke (1554–1628). Greville was an aristocrat, courtier, statesman, sailor, soldier, spymaster, literary patron, dramatist, historian and poet. He was educated at Shrewsbury School, where he met his lifelong friend Sir Philip Sidney, and Jesus College, Cambridge. He was Clerk to the Council of Wales and the Marches, Treasurer of the Navy, and from 1614 to 1621, Chancellor of the Exchequer. After the death of his father in 1606, Fulke became Recorder of Stratford-upon-Avon and he held that post until his own death in 1628.

In The Truth Will Out, published in 2005, Brenda James, a part-time lecturer at the University of Portsmouth, and Professor William Rubinstein, professor of history at Aberystwyth University, argue that Henry Neville, a contemporary Elizabethan English diplomat and distant relative of Shakespeare, is possibly the true author of the plays. Neville's career placed him in the locations of some of the plays at approximately the dates of their authorship.

In a March 2007 lecture at the Smithsonian Institution, John Hudson proposed a new authorship candidate, the poet Emilia Lanier (1569–1645), the first woman in England to publish a book of poetry, Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum (1611). A. L. Rowse had already linked Lanier to Shakespeare in 1973, proposing Lanier as the "dark lady" of the Sonnets.[226] Lanier was born in London, into a family of probable Marrano Jewish extraction, who worked as musicians. They came from Venice and were of Moorish ancestry. Hudson posited that Lanier fits many aspects of the biographical profile implied by the plays.[227] She was also the longterm mistress of Lord Hunsdon, the man in charge of the English theatre and the patron of the Lord Chamberlain's Men.[228] Hudson proposed that Lanier lived as a hidden Jew despite her nominal Christianity; this explained what he considered to be Hebrew and Jewish religious allegories in the plays. Also, unlike Shakespeare, she died poor, depised, lacking honour and proud titles, as described in Sonnets numbers 37, 29, 81, 111 and 25.

Francis Carr proposed that Francis Bacon was both Shakespeare and the author of Don Quixote.[229] A 2007 film called Miguel and William, written and directed by Inés París, explores the parallels and alleged collaboration between Cervantes and Shakespeare.[230]

Other candidates proposed include Mary Sidney.[231]; Sir Edward Dyer; or Roger Manners, 5th Earl of Rutland (sometimes with his wife Elizabeth, daughter of Sir Philip Sidney, and her aunt Mary Sidney, Countess of Pembroke, as co-authors).[232] Malcolm X argued that Shakespeare was actually King James I.[233]